Mark 9:38-50

“Teacher,” said John, “we saw someone driving out demons in your name and we told him to stop, because he was not one of us.”

“Do not stop him,” Jesus said. “For no one who does a miracle in my name can in the next moment say anything bad about me, for whoever is not against us is for us. Truly I tell you, anyone who gives you a cup of water in my name because you belong to the Messiah will certainly not lose their reward.

If anyone causes one of these little ones—those who believe in me—to stumble, it would be better for them if a large millstone were hung around their neck and they were thrown into the sea. If your hand causes you to stumble, cut it off. It is better for you to enter life maimed than with two hands to go into hell, where the fire never goes out. And if your foot causes you to stumble, cut it off. It is better for you to enter life crippled than to have two feet and be thrown into hell. And if your eye causes you to stumble, pluck it out. It is better for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye than to have two eyes and be thrown into hell, where

‘the worms that eat them do not die,

and the fire is not quenched.’

Everyone will be salted with fire. Salt is good, but if it loses its saltiness, how can you make it salty again? Have salt among yourselves, and be at peace with each other.”

Today's reading is challenging,

because it warns us about a stark contrast between those who are working for

good and those who are working for evil. And on both sides Jesus uses dramatic, hyperbolic language to challenge us

to expand our understanding and shake us out of our complacency. There are times, though, when we need shaking

up and being faced with the importance of the choices we can make for good or

bad. Let us remember the words of the Gospel, that

“God did not send his Son

into the world to condemn the world, but to save”, so let us take this

challenge and learn from it, and grow from it, and not despair.

The disciples come to Jesus to

complain about a person who was not a recognised disciple calling on the name

of Jesus to drive out demons. And Jesus corrects them, saying "for no one

who does a miracle in my name can in the next moment speak against me, for

whoever is not against us is for us". Jesus is expanding the boundaries, of

who can be called a disciple, saying God is not bounded by our

organisations and categories, but reaches out to all those who want to put

their faith in him.

And the Church has not always

been good at remembering this verse. The Spirit goes ahead of us, finding those

people with a heart turned towards God. Too often though, the Church has

rejected people seeking to act outside the current accepted structures, out of

fear and concern about what people might say or do, out of a desire to keep the mission

of God under control. But God is not under our control or command. Always the

Holy Spirit is going ahead of us and inspiring new people, in different ages

and place and ways. Perhaps we should see our mission more as going out and

finding those people the Spirit is inspiring and offering our help.

Let me tell you a true story. 300

years ago, the Church in England was in a bad state. Personal faith and

commitment were rare among ordinary people, clergy were not appointed for their

spirituality and dedication to God, but because they were sons of minor gentry

who didn't have another job; the government and aristocracy saw the Church as a

means of controlling society and ensuring the poor and working people did not

get the wrong ideas. Then within this environment came

a man called John Wesley, who went on to found the Methodist movement. Wesley

was a remarkable man. By upbringing and training he was a stiff high-churchman,

a Tory and a conservative, who believed church should be conducted by the book,

by rules and order. But then one day at a church service in Aldersgate London

the Holy Spirit moved in him and from then on he was a different man.

He began preaching outside of

physical church buildings, something that was unheard of and basically illegal

at the time. He preached in fields and in graveyards, and on the street and at

factories, anywhere people would stop and listen. He preached about the Love

and Forgiveness of God that could change the life of any man or woman or child.

He inspired people to seek a life of genuine holiness, giving up violence and

drunkenness, and hatred and bitterness, and embracing a Christian life of love

and faith. He encouraged groups of working-class people to form their own

religious communities, he encouraged ordinary people to preach and teach

without clergy being involved, he cast aside every High-Church principle he had

treasured of what respectable conduct looked like to reach people with the

message of God.

He and his followers suffered

abuse and persecution: they were barred from churches, dragged before

magistrates and rejected by polite society. They carried on day after day, for

50 years. He spoke out condemning slavery, long before that was a popular

position, and he supported women in preaching and leading, many years before

that became accepted across society. When he died, he left behind 140,000

people dedicating their lives to the Good News of Jesus Christ, 500 largely

working class lay preachers, and not a penny to his name. The tens of millions

of Methodists worldwide are today a testament to his selfless love of Jesus

Christ.

John Wesley was faithful to the

Church of England his whole life. He never rejected the Church, he never wanted

the movement he started to be separate from the Church of England, but he would

not, he could not allow the constraining rules of the Church in his day to stop

him from carrying out the mission of God's Spirit. Caught between his loyalty

to the Church and his loyalty to God, he chose God. But what of the Church? By turning its back on the

Methodist movement, by refusing to judge a tree by its fruit, by refusing to

see what God's Spirit was doing, the Church of England lost out on a great

opportunity to be renewed and revived, and after John Wesley died Methodists

and Anglicans in Britain and around the world became more divided, and sadly

that divide is still with us today. How much energy and hope and blessing has

been squandered in this country because Church leaders were not willing to

accept that God was going ahead of them? And the lesson was there in the Gospel

the whole time - “For whoever is not against us is for us."

At least then do not let us make

the same mistake. I think to some degree we have finally learned the lesson. I

hope and expect there is not anyone here today who would say you have to be an

Anglican, or a Methodist, or a Baptist, to be a Christian. No, rather the one

who has faith in God through Jesus Christ, and does what the Lord Jesus,

commanded, in faith, hope and love, that person is truly a Christian. Let us

always be open and humble, willing to consider new ideas, new ways that God

might be moving, and inspiring people: to set up a ministry, a Christian

community group, a charity, a YouTube channel, an entire church. Let us always

be open to help where we can, for "by their fruit you shall know them".

At the same time, we should not

abandon our scepticism, we should always be willing to ask questions, about

plans, intentions; and we should always be willing to answer them humbly and

peacefully. If we asking people to give us their money, their time, their

trust, then we should welcome the chance to reasonably justify ourselves.

Scrutiny is not persecution, we should welcome the chance to demonstrate that

we act from the right motives, and with ideas that can work. We should be

willing to consider that I myself, might be wrong, not just some other person.

Because, in the second half of

our reading, we see what it can mean, at the worst, when we are not humble

enough to accept that we might be wrong, where we reject scrutiny, and fail in

our responsibility to be accountable to one another. "“If anyone causes

one of these little ones who believe in me to stumble, it would be better for

them if an enormous rock were tied around their neck and they were thrown into

the sea." I cannot hear those words without

thinking of the terrible scandals of abuse of children and adults that have

taken place in many of the institutions of our society: the BBC, Football

Clubs, Social Services, the Police, Schools, and in Churches. Lives have been devastated.

People who trusted in Church ministers and leaders to protect them and nurture

them, have been betrayed in the most appalling way; and when victims have come

forward to warn people about the predators in our midst, wolves in sheep's

clothing, often they have been ignored or side-lined, and more innocent people

have been victimised.

It would be better for those

predators, and better for those people who enabled them, better for those

people who allowed abuse to continue, if they had enormous rocks tied around

their necks, and they threw themselves into the sea. Every time we discuss

Safeguarding at church meetings, I hear those words. God's anger and wrath

burns against the evil done to his children. How do these things happen though?

There are a small minority of wolves in sheep's clothing, of predators, and

they are very good at hiding themselves, and they could be anywhere. They are priests and school

teachers and social workers and doctors and parents and university professors

and policemen and a hundred other things. They can appear anywhere, but they

are very few in number. But for each predator there must be many people who do

not ask questions, who do not keep their eyes open, who do not scrutinise what

is happening around them, who give in to inertia, and so become accomplices to

evil.

And I suspect we would be

terrified by how easy a thing it is to do. You're a busy person, incredibly

busy, you're constantly swapping between a dozen different things: work,

family, social events, community groups. You've got a list of people you need

to speak to, another list to email, text, WhatsApp, Facebook messenger, all

going off throughout the day; and at the same time, you're trying to remember

to post a birthday card, and a dozen items to pick up from the shops. Amid all that you receive one

message asking to meet and talk about something, some kind of complaint about a

person you know. You know the person, you've known them for years, they've

always been reliable, cheerful, and caring. They are a friend, and you feel

loyalty to them, warmth, trust. You don't know the details, you can't believe

it, and you don't know what you should or could do, so you put it to one side

for now. And before you realise there's another email, another meeting, another

responsibility, and without ever meaning it, the message, the allegation, the

warning, is forgotten and the chance is missed.

It has happened, you have become

an enabler of evil, and "it would be better for them if a large millstone

were hung around their neck and they were thrown into the sea." There are

other ways this can happen as well. Perhaps you do not receive a message about

potential abuse, perhaps you just notice something out-of-place, something that

makes you uncomfortable, and you brush it off and never mention it to anyone.

That too can be a way we fail in our duty to provide a safe and loving

environment, for children, for vulnerable adults, for everyone. You may never

be in that situation, but if you are, if you notice something, if you are told

something, you may be the only one, which is why it is so important that you

know how to act, and you do. That is why we have safeguarding

procedures, and training, and a safeguarding officer - currently Josie Gadsby -

so in the rare event we can act to prevent evil happening among us, we know

what to do, and we do it. We must all be prepared; and we must make clear, that

if you notice anything inappropriate, or if you are suffering anything that is

wrong, this is a safe environment to come forward and speak out, knowing it

will be taken seriously and acted upon.

The terrible evil of personal

abuse, is, certainly, not the only form of sin, though it is one of the most terrible.

Often sin comes in smaller, more mundane forms: anger, greed, self-obsession,

bitterness, thoughtlessness, dishonesty. In small doses these make up the

everyday failures which mark our lives, alongside, of course, all the good we

do. But the bad does not wash out the good, nor the good the bad. Still, we

harm and do injustice to those around us, often in ways we are not even aware

of, but the effect is the same. And smaller

doses combine into doses that may then be fatal. All the evils of our world, up to the big lies that poison whole nations, originate in these same mundane sins, that combine and grow.

I was reminded of this again

recently, when I came to church to see the 'Camino to COP' walkers, who are

walking from London to Glasgow to beg Global Leaders gathering there to take

serious action against the threat of Global Warming. I have to say I was deeply

moved by their pilgrimage, by their description of walking and singing and

laughing and hoping together on this great journey across our country. It was also a reminder that the

damage done by Global Warming, which we are seeing in increased wildfires, and

flooding, retreating polar icecaps, and other symptoms in recent years, and

which threatens both humans and animal species. I think of not just Global

Warming, but the Plastic Pollution problem, the destruction of the Rainforests,

the devastation of fishing stocks, of air pollution and all the forms of damage

we have done and are doing to our Environment.

The church service I grew up

with, Common Worship, had some wonderful words in the Confession of our sins

that stick with me today: through negligence, through weakness, through our own

deliberate fault. Sometimes you hear people talk about sins of commission and

omission: that's what you do, and what you don't do; what you say, and what you

don't say. Each kind is as important as the other, and environmental problems

are an important example of how they can also come mixed together. Nobody gets

up in the morning and says, "Today I'm going to screw the planet",

but at the same time, we all contribute, through the consumption and lifestyles

we lead, the plastic we throw away, the cars we drive, the flights we take, the

palm oil in the food we eat, etc. We don't do it to do harm, but we all do it,

and we do cause harm.

"If your hand causes you to

stumble, cut it off. It is better for you to enter Eternal Life maimed than

with two hands go into hell. And if your foot causes you to stumble, cut it

off. It is better to enter Eternal Life crippled than have two feet and be

thrown into hell. And if your eye causes you to stumble, pluck it out. Better

for you to enter the kingdom of God with one eye, than to have two eyes and be

thrown into hell"

Strong words, words designed to

shock and startle us, that would have been just as horrifying to Jesus'

original audience. But not words meant to be taken literally. Often Jesus talks

in parables and metaphors to provoke deeper thought and reflection, and that is

what he's doing here. But only because it is not the hand, or the foot, or the

eye that causes you to stumble: it is the heart, it is me, or you. If I curse someone

is it my mouth who sins? No, it is me. If I kick someone in anger, is it my

foot that has sinned? No, of course, it is me. And though with God's grace I

try to fight sin in one part of my heart and my life, it is still there in

another, and another.

Maybe, then, I should conclude

these words are just windy rhetoric, which can be easily ignored. No, they most

certainly are not. They are incredibly, deadly serious. Well then, maybe there

is nothing left to do but despair, since sin is everywhere. No, my friends, not

that either. We cannot ignore evil, and we cannot minimise it, and we cannot

give in to despair because of it. We have another option, because we are not

alone. We could never free ourselves from the grip of sin by our own power, but

we do not need to.

Jesus Christ, who is God of God,

was born a man, lived and died as one of us, and because he is God himself,

rose again free of sin and death and shame; and through Jesus Christ we have

the gift of forgiveness, grace and freedom from our sins. We are joined with

the very Power of God, and the Holy Spirit comes to live within us. We have a

terrible responsibility, to fight against sin and evil every day in our own

lives, but never alone, with the Grace and Power of God who walks alongside us

every step of the way, knowing he sees us as we really are and loves us anyway,

enough to die for us that we may live.

Jesus Christ, my Master and my Friend, walks alongside us but we have help from another source too. The Holy

Spirit is moving around us and ahead of us, stirring people up, and if we can

keep up with the Spirit then we are in for a remarkable adventure. I spoke

earlier about John Wesley and the incredible life he had, one that still

touches tens of millions of people, Methodists and others, around the world

today. He was not the first, the man in

our reading today, who was exorcising demons, he probably wasn't even the

first, and neither will either of them be the last. The Holy Spirit is moving today, and so

I still have hope, no matter what you read in the papers, what you read on

Facebook, what you read online, thanks be to God, there is always hope. The

powers of sin and death and evil and fear in our own lives and in our world are

terrible, but they are nothing against the power of Jesus Christ.

Amen.

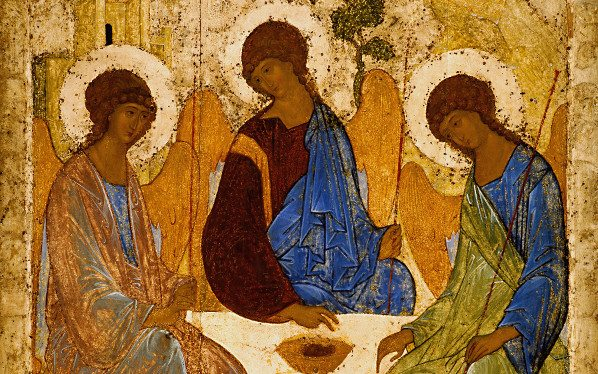

Image borrowed with thanks from: https://catholic-daily-reflections.com/2020/06/11/avoidance-of-sin-2/